Methods of contour integration

In the mathematical field of complex analysis, contour integration is a method of evaluating certain integrals along paths in the complex plane.[1][2][3]

Contour integration is closely related to the calculus of residues,[4] a methodology of complex analysis.

One use for contour integrals is the evaluation of integrals along the real line that are not readily found by using only real variable methods.[5]

Contour integration methods include

- direct integration of a complex-valued function along a curve in the complex plane (a contour)

- application of the Cauchy integral formula

- application of the residue theorem.

One method can be used, or a combination of these methods, or various limiting processes, for the purpose of finding these integrals or sums.

Contents

|

Direct methods

Direct methods involve the calculation of the integral by means of methods similar to those in calculating line integrals in several-variable calculus. This means that we use the following method:

- parametrizing the contour

- The contour is parametrized by a differentiable complex-valued function of real variables, or the contour is broken up into pieces and parametrized separately

- substitution of the parametrization into the integrand

- Substituting the parametrization into the integrand transforms the integral into an integral of one real variable.

- direct evaluation

- The integral is evaluated in a method akin to a real-variable integral.

Example

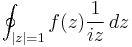

A fundamental result in complex analysis is that the contour integral of z−1 is 2πi, where the path of the contour is taken to be the unit circle traversed counterclockwise (or any Jordan curve about 0). In the case of the unit circle there is a direct method to evaluate the integral

In evaluating this integral, use the unit circle |z| = 1 as contour, parametrized by z(t) = eit, with t ∈ [0, 2π], then dz / dt = i e it and

which is the value of the integral.

Applications of integral theorems

Applications of integral theorems are also often used to evaluate the contour integral along a contour, which means that the real-valued integral is calculated simultaneously along with calculating the contour integral.

Integral theorems such as the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem are generally used in the following method:

- a specific contour is chosen:

- The contour is chosen so that the contour follows the part of the complex plane that describes the real-valued integral, and also encloses singularities of the integrand so application of the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem is possible

- application of the Cauchy–Goursat theorem

- The integral is reduced to only an integration around a small circle about each pole.

- application of the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem

- Application of these integral formula gives us a value for the integral around the whole of the contour.

- division of the contour into a contour along the real part and imaginary part

- The whole of the contour can be divided into the contour that follows the part of the complex plane that describes the real-valued integral as chosen before (call it R), and the integral that crosses the complex plane (call it I). The integral over the whole of the contour is the sum of the integral over each of these contours.

- demonstration that the integral that crosses the complex plane plays no part in the sum

- If the integral I can be shown to be zero, or if the real-valued integral that is sought is improper, then if we demonstrate that the integral I as described above tends to 0, the integral along R will tend to the integral around the contour R + I.

- conclusion

- If we can show the above step, then we can directly calculate R, the real-valued integral.

Example (I)

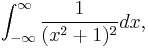

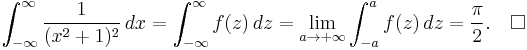

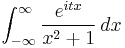

Consider

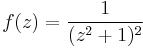

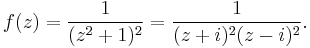

To evaluate this integral, we look at the complex-valued function

which has singularities at i and −i. However, we will want to choose a contour that will enclose the real-valued integral, so we choose a semicircle like the one shown on the left, which we will let expand as to contain the whole real axis (a will tend to infinity). Call this contour C.

Now, there are two ways of proceeding, using the Cauchy integral formula or by the method of residues.

Using the Cauchy integral formula

Note that:

thus

Furthermore observe that

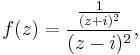

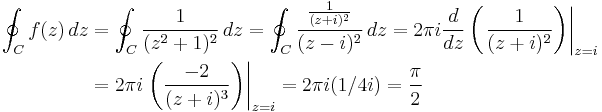

Since the only singularity in the contour is the one at i, then we can write

which puts the function in the form for direct application of the formula. Then, by using Cauchy's integral formula,

(We take the first derivative, in the above steps, because the pole is a second-order pole. That is, (z − i ) is taken to the second power, so we employ the first derivative of ƒ(z). If it were (z − i ) taken to the third power, we would use the second derivative and divide by 2!, etc. The case of (z − i ) to the first power corresponds to a zero order derivative—just ƒ(x) itself.)

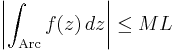

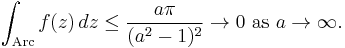

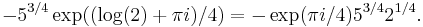

If we call the arc of the semicircle Arc, we need to show that the integral over Arc tends to zero as a tends to infinity — using the estimation lemma

where M is an upper bound on |ƒ(z)| along the Arc and L the length of Arc. Now,

So

Using the method of residues

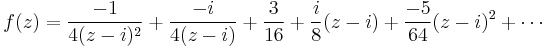

Consider the Laurent series of f(z) about i, the only singularity we need to consider. We then have

(See Sample Laurent Calculation from Laurent series for the derivation of this series.)

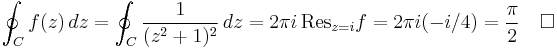

It is clear by inspection that the residue is −i/4 (to see this, imagine that the above equation were multiplied by z − i, then both sides integrated via the Cauchy integral formula—only the second term would integrate to a non-zero quantity), so, by the residue theorem, we have

Thus we get the same result as before.

Contour note

As an aside, a question can arise whether we do not take the semicircle to include the other singularity, enclosing −i. To have the integral along the real axis moving in the correct direction, the contour must travel clockwise, i.e., in a negative direction, reversing the sign of the integral overall.

This does not affect the use of the method of residues by series.

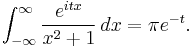

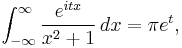

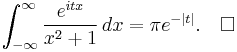

Example (II) – Cauchy distribution

The integral

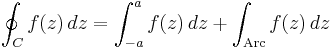

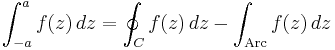

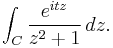

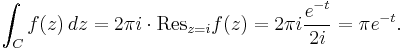

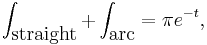

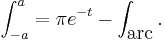

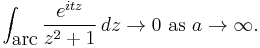

(which arises in probability theory as (a scalar multiple of) the characteristic function of the Cauchy distribution) resists the techniques of elementary calculus. We will evaluate it by expressing it as a limit of contour integrals along the contour C that goes along the real line from −a to a and then counterclockwise along a semicircle centered at 0 from a to −a. Take a to be greater than 1, so that the imaginary unit i is enclosed within the curve. The contour integral is

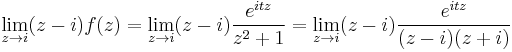

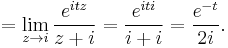

Since eitz is an entire function (having no singularities at any point in the complex plane), this function has singularities only where the denominator z2 + 1 is zero. Since z2 + 1 = (z + i)(z − i), that happens only where z = i or z = −i. Only one of those points is in the region bounded by this contour. The residue of f(z) at z = i is

According to the residue theorem, then, we have

The contour C may be split into a "straight" part and a curved arc, so that

and thus

It can be shown that if t > 0 then

Therefore if t > 0 then

A similar argument with an arc that winds around −i rather than i shows that if t < 0 then

and finally we have this:

(If t = 0 then the integral yields immediately to real-valued calculus methods and its value is π.)

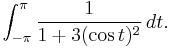

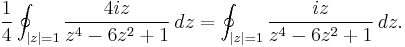

Example (III) – trigonometric integrals

Certain substitutions can be made to integrals involving trigonometric functions, so the integral is transformed into a rational function of a complex variable and then the above methods can be used in order to evaluate the integral.

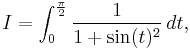

As an example, consider

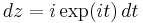

We seek to make a substitution of z = eit.

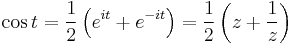

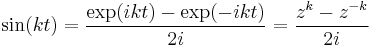

Now, recall

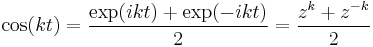

and

Taking C to be the unit circle, we substitute to get:

We use the Cauchy integral formula. Factorize the denominator:

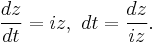

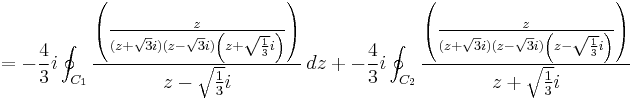

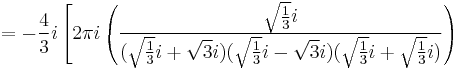

The singularities then to be considered are at 3−1/2i, −3−1/2i. We can now reduce the integral:

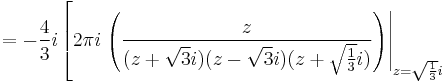

where C1 is a small circle about 3−1/2i, and C2 is a small circle about −3−1/2i. We can now apply the formula:

Example (IIIa) trigonometric integrals, the general procedure

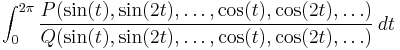

The above method may be applied to all integrals of the type

where P and Q are polynomials, i.e. a rational function in trigonometric terms is being integrated.

The trick is to use the substitution  where

where  and hence

and hence

This substitution maps the interval ![[0, 2\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/58c9a5de0cb1a343ae0acd1fb191eea1.png) to the unit circle. Furthermore,

to the unit circle. Furthermore,

and

so that a rational function ƒ(z) in z results from the substitution, and the integral becomes

which is in turn computed by summing the residues of  inside the unit circle.

inside the unit circle.

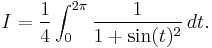

The image at right illustrates this for

which we now compute. The first step is to recognize that

The substitution yields

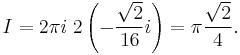

The poles of this function are at 1 ± √2 and −1 ± √2. Of these, 1 + √2 and −1 −√2 are outside the unit circle (shown in red, not to scale), whereas 1 − √2 and −1 + √2 are inside the unit circle (shown in blue). The corresponding residues are both equal to −i√2/16, so that the value of the integral is

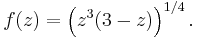

Example (IV) – branch cuts

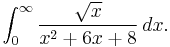

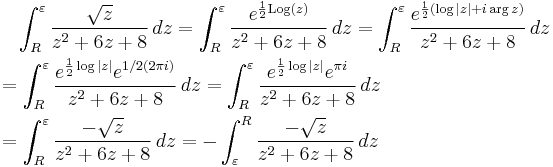

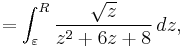

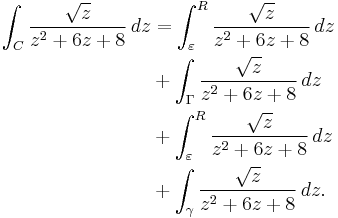

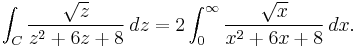

Consider

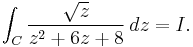

We can begin by formulating the complex integral

We can use the Cauchy integral formula or residue theorem again to obtain the relevant residues. However, the important thing to note is that z1/2 = e1/2·Log(z), so z1/2 has a branch cut. This affects our choice of the contour C. Normally the logarithm branch cut is defined as the negative real axis, however, this makes the calculation of the integral slightly more complex, so we define it to be the positive real axis.

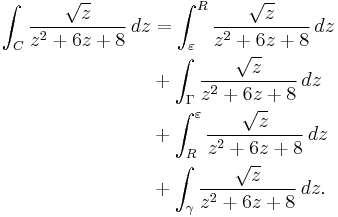

Then, we use the so-called keyhole contour, which consists of a small circle about the origin of radius ε say, extending to a line segment parallel and close to the positive real axis but not touching it, to an almost full circle, returning to a line segment parallel, close, and below the positive real axis in the negative sense, returning to the small circle in the middle.

Note that z = −2 and z = −4 are inside the big circle. These are the two remaining poles, derivable by factoring the denominator of the integrand. The branch point at z = 0 was avoided by detouring around the origin.

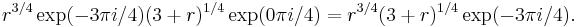

Let γ be the small circle of radius ε, Γ the larger, with radius r, then

Since z1/2 = e1/2 Log(z), on the contour outside the branch cut, we have gained 2π in argument along γ (by Euler's Identity,  represents the unit vector, which therefore has

represents the unit vector, which therefore has  as its log. This

as its log. This  is what is meant by the argument of z. The coefficient of 1/2 forces us to use 2 times

is what is meant by the argument of z. The coefficient of 1/2 forces us to use 2 times  ), so

), so

simplifying,

and then

It can be shown that the integrals over Γ and γ both tend to zero as ε tends to zero and R tends to infinity, by an estimation argument above. Thus, then,

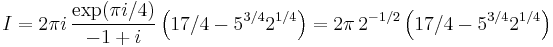

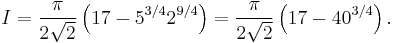

By using the residue theorem or the Cauchy integral formula (first employing the partial fractions method to derive a sum of two simple contour integrals) one obtains

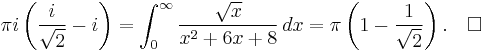

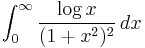

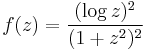

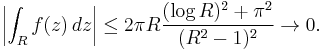

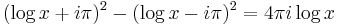

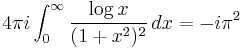

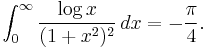

Example (V) – the square of the logarithm

This section treats a type of integral of which

is an example.

To calculate this integral, one uses the function

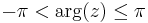

and the branch of the logarithm corresponding to  .

.

We will calculate the integral of ƒ(z) along the keyhole contour shown at right. As it turns out this integral is a multiple of the initial integral that we wish to calculate.

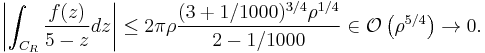

Let R be the radius of the large circle, and r the radius of the small one. We will denote the upper line by M, and the lower line by N. As before we take the limit when R goes to infinity and r to zero. The two contributions from the two circles vanish. For example, one has the following upper bound with the ML-lemma:

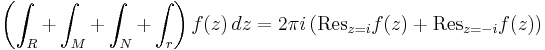

By the Cauchy residue theorem we thus have

or

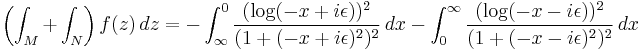

It remains to calculate the contributions of M and N. We set  on M and

on M and  on N, with

on N, with  This gives

This gives

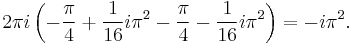

or

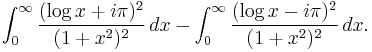

To conclude, one observes that

and thus

which gives

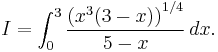

Example (VI) – logarithms and the residue at infinity

We seek to evaluate

This requires a close study of

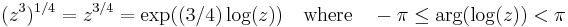

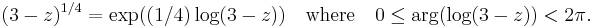

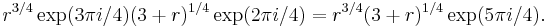

We will construct f(z) so that it has a branch cut on [0, 3], shown in red in the diagram. To do this, we choose two branches of the logarithm, setting

and

The cut of z3/4 is therefore ![(-\infty, 0]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f9d75a40b8eadac31117745d2255ef61.png) and the cut of

and the cut of  is

is ![(-\infty, 3]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a344f5a460db11b3918099de2a61ab0d.png) . It is easy to see that the cut of the product of the two, i.e.

. It is easy to see that the cut of the product of the two, i.e.  , is

, is ![[0, 3]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ed9c05fe24c0f49f5d73f494a921e0c4.png) , because f(z) is actually continuous across

, because f(z) is actually continuous across  This is because when

This is because when  and we approach the cut from above, f(z) has the value

and we approach the cut from above, f(z) has the value

When we approach from below, f(z) has the value

But  so that we have continuity across the cut. This is illustrated in the diagram, where the two black oriented circles are labelled with the corresponding value of the argument of the logarithm used in

so that we have continuity across the cut. This is illustrated in the diagram, where the two black oriented circles are labelled with the corresponding value of the argument of the logarithm used in  and

and

We will use the contour shown in green in the diagram. To do this we must compute the value of ƒ(z) along the line segments just above and just below the cut.

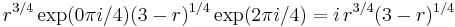

Let  (in the limit, i.e. as the two green circles shrink to radius zero), where

(in the limit, i.e. as the two green circles shrink to radius zero), where  Along the upper segment, we find that

Along the upper segment, we find that  has the value

has the value

and along the lower segment,

It follows that the integral of  along the upper segment is

along the upper segment is  in the limit, and along the lower segment,

in the limit, and along the lower segment,

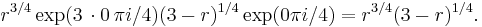

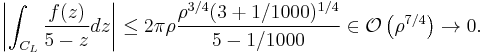

If we can show that the integrals along the two green circles vanish in the limit, then we also have the value of  , by the Cauchy residue theorem. Let the radius of the green circles be

, by the Cauchy residue theorem. Let the radius of the green circles be  , where

, where  and

and  and apply the ML-inequality. For the circle

and apply the ML-inequality. For the circle  on the left, we find

on the left, we find

Similarly, for the circle CR on the right, we have

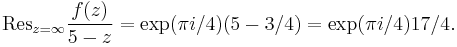

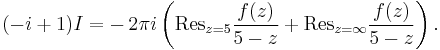

Now using the Cauchy residue theorem, we have

where the minus sign is due to the clockwise direction around the residues. Using the branch of the logarithm from before, clearly

The pole is shown in blue in the diagram. The value simplifies to

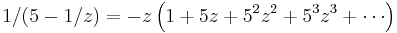

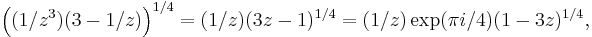

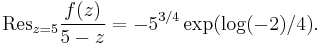

We use the following formula for the residue at infinity:

Substituting, we find

and

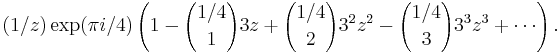

where we have used the fact that  for the second branch of the logarithm. Next we apply the binomial expansion, obtaining

for the second branch of the logarithm. Next we apply the binomial expansion, obtaining

The conclusion is that

Finally, it follows that the value of  is

is

which yields

See also

References and notes

- ^ John Stalker (1998). Complex Analysis: Fundamentals of the Classical Theory of Functions. Springer. p. 77. ISBN 081764038X. http://books.google.com/books?id=yl3GIXd3dFIC&pg=PP12&dq=%22calculus+of+residues%22#PPA77,M1.

- ^ Joseph Bak & Donald J. Newman (1997). Complex Analysis. Springer. Chapters 11 & 12, pp. 130–156. ISBN 0387947566. http://books.google.com/books?id=JX2YSgfZwbYC&pg=PA130&dq=%22contour+integral%22#PPA130,M1.

- ^ Steven George Krantz (1999). Handbook of Complex Variables. Springer. Chapter 2. ISBN 0817640118. http://books.google.com/books?id=aYU2AdF_0dIC&pg=PT13&dq=Calculus++Residues+inauthor:krantz#PPT47,M1.

- ^ Dragoslav S. Mitrinovic & Jovan D. Keckic (1984). The Cauchy Method of Residues: Theory and Applications. Springer. Chapter 2. ISBN 9027716234. http://books.google.com/books?id=-suKhxfPH5AC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22calculus+of+residues%22#PPA5,M1.

- ^ Dragoslav S. Mitrinovic & Jovan D. Keckic (1984). Chapter 5. ISBN 9027716234. http://books.google.com/books?id=-suKhxfPH5AC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22calculus+of+residues%22#PPA108,M1.

Further reading

- Titchmarsh, E.C. (1939), The Theory of Functions (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198533497

- Jean Jacquelin, Marko Riedel, Branche univalente, Les-Mathematiques.net, in French.

- Marko Riedel et al., Problème d'intégrale, Les-Mathematiques.net, in French.

- Various authors, sin límites ni cotas, es.ciencia.matematicas, in Spanish.

![\begin{align}

\oint_C {1 \over z}\,dz & {} = \int_0^{2\pi} {1 \over e^{it}} \, ie^{it}\,dt = i\int_0^{2\pi} 1 \,dt \\

& {} = \Big[t\Big]_0^{2\pi} i=(2\pi-0)i = 2\pi i,

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2dd616d0645bb9a493429052fa00f68c.png)

![\begin{align}

& {} \quad \oint_C {1 \over 1 %2B 3 ({1 \over 2} (z%2B{1 \over z}))^2} \,{dz\over iz} \\[6pt]

& = \oint_C {1 \over 1 %2B {3 \over 4} (z%2B{1 \over z})^2}{1 \over iz} \,dz

= \oint_C {-i \over z%2B{3\over 4}z(z%2B{1\over z})^2}\,dz \\[6pt]

& = -i \oint_C { 1 \over z%2B{3\over 4}z(z^2%2B2%2B{1\over z^2})} \,dz \\[6pt]

& = -i \oint_C {1\over z%2B{3\over 4}(z^3%2B2z%2B{1 \over z})} \,dz = -i \oint_C {1 \over {3\over 4 }z^3%2B{5 \over 2}z%2B{3 \over 4z}} \,dz \\[6pt]

& = -i \oint_C {4 \over 3z^3%2B10z%2B{3\over z}}\,dz = -4i \oint_C {1 \over 3z^3%2B10z%2B{3\over z}}\,dz \\[6pt]

& = -4i \oint_C { z \over 3z^4%2B10z^2%2B3 } \,dz.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0414b4c5b291071263bdf882d4aed2f4.png)

![\begin{align}

& = -4i \oint_C { z \over 3z^4%2B10z^2%2B3 } \,dz = -4i \oint_C {z \over 3(z^2%2B3)(z^2%2B1/3)}\,dz \\[6pt]

& = -4i \oint_C {z \over 3(z%2B\sqrt{3}i)\left(z-\sqrt{3}i\right)\left(z%2B\sqrt{1\over 3}i\right)\left(z-\sqrt{1\over 3}i\right)}\,dz \\[6pt]

& = -{4\over 3}i \oint_C {z \over (z%2B\sqrt{3}i)(z-\sqrt{3}i)\left(z%2B\sqrt{1\over 3}i\right)\left(z-\sqrt{1\over 3}i\right)}\,dz.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/893c321e47ef29512fb31f4846831777.png)

![\left. {} %2B 2\pi i \left.\left({z \over (z%2B\sqrt{3}i)(z-\sqrt{3}i)(z-\sqrt{1\over 3}i)}\right)\right|_{z=-\sqrt{1 \over 3}i}

\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b8305746143787229287b68c95fe80cc.png)

![\left. {} %2B2\pi i \left( { -\sqrt{1\over 3}i \over (-\sqrt{1\over 3}i%2B\sqrt{3}i)(-\sqrt{1\over 3}i-\sqrt{3}i)(-\sqrt{1\over 3}i-\sqrt{1\over 3}i } \right)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f2045c207763c203357a2f103d31fa64.png)

![= -{4\over 3}i \left[ 2\pi i

\left( {\sqrt{1\over 3}i \over ({4 \over \sqrt{3}}i)(-{2 \over \sqrt{3}}i)({2 \over \sqrt{3}}i)} \right) %2B

2 \pi i \left( {-\sqrt{1\over 3}i \over ({2 \over \sqrt{3}}i)(-{4 \over \sqrt{3}}i)(-{2 \over \sqrt{3}}i)} \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2224fae1af15dedd1ec74fa745a26d05.png)

![= -{4\over 3}i \left[

2\pi i \left( {\sqrt{1\over 3}i \over i({4 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})} \right) %2B

2\pi i \left( {-\sqrt{1\over 3}i \over -i({2 \over \sqrt{3}})({4 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})} \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/aa1b3aad32688d955a3109246d17c6f7.png)

![= -{4\over 3}i \left[

2\pi i \left( {\sqrt{1\over 3} \over ({4 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})} \right) %2B

2\pi i \left( {\sqrt{1\over 3} \over ({2 \over \sqrt{3}})({4 \over \sqrt{3}})({2 \over \sqrt{3}})} \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6cd8a55253069f4fd8f987fe6423fe7a.png)

![= -{4\over 3}i \left[

2\pi i \left( { \,\sqrt{1\over 3} \,\over {16 \over 3\sqrt{3}} } \right) %2B

2\pi i \left( {\, \sqrt{1\over 3} \,\over {16 \over 3\sqrt{3}} } \right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1d8200c753f6ae5c1121dd0237a10c55.png)

![= -{4\over 3}i \left[2 \pi i \left({3\over 16}\right) %2B 2 \pi i \left({3\over 16}\right)\right] = \pi.\quad\square](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/52caa1349b78cbf740dd49a72d0a2d5a.png)

![\mathrm{Res}_{z=\infty} h(z) =

\mathrm{Res}_{z=0} \Big[- \frac{1}{z^2} h\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\Big].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a8cae15a40bca61381625335bbccf44d.png)